Description:

I thank the Committee for its invitation to testify on the implementation of the North Korean Human Rights Act of 2004, re-authorized in 2008. I represent, as Executive Director, the Committee for Human Rights in North Korea, a bi-partisan, Washington-based research and advocacy organization devoted to the advancement of the human rights of the people of North Korea. I should add that my views in all likelihood do not reflect the views of every member of the Board.

I speak here today as an individual who has spent many years working on this issue, including service here in the House of Representatives over ten years ago as the senior defense and foreign policy advisor of the Policy Committee, during which time I worked with this Committee on a number of matters relating to North Korea. This included the DoD Authorization Act which established the role of North Korea Policy coordinator in 1998, the report of the Speaker‟s Special Advisory Group on North Korea in 1999 (available at:

http://www.fas.org/nuke/guide/dprk/nkag-report.htm), and the first steps that were taken toward

the enactment of the North Korean Human Rights Act which became law in 2004. I know from first-hand experience the deep interest and profound dedication of members and staff of this Committee, on North Korean human rights issues, and applaud your consistent efforts to protect the people of North Korea from the human rights abuses afflicted on them by their own regime.

In 2009, our co-chair the late Stephen J. Solarz, a distinguished former member of Congress and chairman of an important Subcommittee of this Committee, convened a group of human rights specialists in Washington to discuss priorities for addressing the human rights crisis in North Korea. Under his leadership, we developed a set of ten policy recommendations, a key one of which was to enhance the implementation of the North Korea Human Rights Act.

We recommended that the administration establish a specific office with the responsibility for implementing the NKHRA refugee resettlement mandate. We advised that it was critical for the State Department to better educate embassy personnel in countries of asylum for North Korean refugees to understand the circumstances facing these refugees and the nature of the North Korean regime. We also recommended an increase in the staffing levels of U.S. personnel, particularly Korean speakers, in the region‟s embassies and consulates to handle North Korean refugee resettlement issues. Further, we recommended that the State Department establish a hotline in coordination with the UNHCR and the Republic of Korea, so that North Korean refugees in danger would have ways to contact those who can offer them immediate protection.

The Enforcement of the North Korea Human Rights Act

Madame Chairman, in your letter of invitation, you specifically requested that I address the number of North Korean refugees that have been resettled in the United States, and certain questions regarding the implementation of the NKHRA. Regarding the number of refugees, I must rely on figures from the Department of State and information from other organizations, but I am informed that 120 individuals have been given asylum in the United States since the enactment of the NKHRA. This number seems very small, and of course it remains very difficult for North Korean refugees to gain access to any American or international official who could hear their requests for permission to come to the United States. The number of refugees who have made it to South Korea in recent years has been growing and is very encouraging. The government of the Republic of Korea is to be commended for their attention to the plight of these people and its efforts to help them adjust to South Korean society. The problem, of course, is China‟s policy of repatriating North Koreans without giving them access to a screening procedure to determine whether they are refugees. Increasingly, we hear reports of Chinese officials turning a blind eye toward North Korean attempts to recapture North Korean escapees in China, and in fact, there is growing evidence of Chinese complicity in these North Korean violations of Chinese jurisdictional sovereignty. Changing China‟s attitude toward North Korean refugees should be an important objective of U.S. policy toward China.

Persuade China to Respect the Rights of North Korean Refugees

North Koreans who attempt to move about inside their own country in search of food, medicine and jobs have often been arrested and detained. At the same time, their government refuses to acknowledge the fundamental right of people to leave their country and return to it. For more than two decades, North Koreans have been fleeing their country because of economic deprivation and political persecution. Whether they are forced back to North Korea or return voluntarily, they are subjected to detention, punishment, imprisonment, and sometimes execution.

Because of their reasonable fear of persecution on return to North Korea, all of the people who flee North Korea may well qualify as refugees sur place and warrant the protections that international law requires for refugees. International law, particularly the 1951 UN Refugee Convention, strictly and specifically prohibits forced repatriation of a person to another state where there are substantial grounds for believing that they would be in danger of being subjected to torture or persecution.

Yet China repatriates North Koreans without affording them any access to a screening process whereby their claims for refugee status could be assessed. The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) has often requested to have access to North Koreans in order to determine their status, but China has restricted UNHCR‟s access and North Koreans‟ access to UNHCR‟s offices in Beijing. The United States should lend its full support to UNHCR‟s appeals and mobilize other governments to do likewise in order to make sure that the provisions of the 1951 Refugee Convention are upheld and the work of this important UN agency enhanced. The United States should also raise with China the need to respect the rights of North Korean women who stay in China to raise their families, and afford these residents legal status for themselves and their children. Repatriation of North Koreans not only leads to their imprisonment and other abuses, it also encourages trafficking, forcing North Korean women who fear repatriation into forced marriages, prostitution, and physical and psychological abuse.

Establish a First Asylum Program for North Korean Refugees

There is no reason for China to have to bear the burden of resettling all North Korean refugees. The United States should work with South Korea and countries around the world to establish multilateral First Asylum arrangements, as was done for the Vietnamese boat people in the late 1970s. Arrangements should be negotiated with countries in the region which will provide temporary asylum to these refugees with the assurance that the refugees will be permanently resettled elsewhere.

South Korea should be supported in its efforts to grant asylum to North Korean refugees who reach its embassies and consulates abroad since it is the country whose Constitution protects the rights of North Koreans fleeing abroad. Given the special connections between Mongolia and the Koreas, the government of Mongolia should be encouraged to play a more active role in providing asylum and facilitating resettlement to a third country. The United States should also initiate the development of an international plan with UNHCR for a potential refugee crisis in the event of political destabilization in North Korea.

Recognize the Need to Develop Policies To Attract Critically Important High-Level Defectors from North Korea

The vast majority of refugees from North Korea are clearly victims of an oppressive state—they are poorly-educated, under-nourished, impoverished, and in many cases, psychologically broken. They may well choose to restart their lives among their kinsmen in South Korea where they have some common understanding of the language and culture, and where government programs are in place to facilitate their assimilation. Yet there are tremendous success stories—people who have emerged from their circumstances to be leaders in their new surroundings.

It is very difficult for American policy to fine-tune is an approach that allows people who would like to come to the U.S. at some later point if they so desire, but such policies would reap tremendous benefits.

My organization had the honor of hosting a very well-educated high-level North Korean defector, Mr. Kim Kwangjin, who used his English language fluency to explain the regime‟s corrupt financial practices and provide advice on how U.S. policies could influence the regime‟s behavior for the better. He was able to publish two major reports on political transition and wrote very valuable reports on how information is shared in North Korea, and how North Korea‟s banking system operates during his short two years with us. We would have liked to have seen this incredible national asset to have been given citizenship and a permanent position in the United States, but he had no choice but to return to Seoul this past March to resume his position at a think-tank the South Korean government operates for high-level defectors. There ought to be a better organized effort on the part of the United States to attract defectors of interest and give them an opportunity to speak openly about what they know about the inner workings of the regime.

No one knows better how to bring about reform in North Korea than the defectors from North Korea. Since the election of President Lee Myung Bak, many of them have been given new freedom to share their information and insights. They should are an excellent resource for learning more about how the military, party, security services and government work, current human rights conditions in North Korea, including in prisons, and how to bring about reform.

The United States should also help develop an educated cadre of experts and potential leaders who might later return to North Korea. It should create a scholarship program for study in the United States for North Koreans who have departed, and in some cases expand it to include North Koreans who may be permitted to travel abroad for schooling. Congressman Solarz felt particularly strongly that a program adopted by the United States during the period of Apartheid in South Africa produced a generation of leaders who were prepared to take over the reins of leadership when the opportunity arose.

Provide Essential Information Directly to the People of North Korea

Because the North Korean people are so restricted in the information they receive about their own country and the world outside, the United States should continue to expand radio broadcasting into North Korea and encourage other efforts that provide information directly to the North Korean people in accordance with the NKHRA. The United States should also make known to the North Korean people that their welfare is of great concern to the American people and that the U. S. and other nations are regularly restricted by the North Korean government from providing food aid and other supplies to them. The United States government should use its good offices to persuade neighboring countries to provide locations and assistance for transmission facilities for Radio Free Asia, Voice of America, and defector organizations.

I recommend that the Congress direct the Department of State to provide additional funding and if necessary, technical assistance in financial management, to permit Free North Korea Radio to expand its excellent broadcasts into North Korea. Independent surveys have identified Free North Korea Radio as the most effective way to get information into North Korea.

Run by defectors under the leadership of Kim Seong Min, it has produced the most hard-hitting and effective broadcasts into North Korea, even while facing North Korean assassination attempts targeted against its personnel, political badgering in South Korea, having to move offices repeatedly, and shoe-string budgets with strenuous financial reporting requirements.

Stop the Flow of North Korea’s Ill-gotten Wealth

In order to finance its military programs, security services and loyal elite, the North Korean regime has systematically engaged in international criminal activity including drug trafficking, counterfeiting of goods and currency, and banking and insurance fraud. Although a small office exists in the State Department to coordinate the Proliferation Security Initiative, only a few cases have been pursued rigorously. The pursuit of cases against North Korea is sometimes overcome by other priorities (e.g., the maintenance of a favorable negotiating atmosphere), but the administration should recognize the nexus between these international illicit activities and North Korea‟s abuse of human rights at home and pursue enforcement operations rigorously.

Prepare for Political Transition and Humanitarian Crises in North Korea The impending change of leadership when Kim Jong Il dies presents both a challenge and an opportunity for regional peace and security. The implications for the human rights of North Korea‟s people are profound. Although new leadership may not reverse Kim Jong Il‟s policies overnight, it may prove more receptive to addressing some human rights concerns as a means of signaling to the rest of the world that its intentions are friendly.

In the event of political change in North Korea, international access to the prison camps will need to be given the highest priority. Prisoners constitute a “vulnerable group” to whom food, medicine and shelter should be provided immediately. An orderly departure program from the camps will need to be implemented and resettlement arranged for those whose treatment or condition precludes re-integration into North Korean society. The International Labor Organization (ILO) will need to be brought in to review standards of work at the camps where reports of forced and slave labor and below-subsistence food rations have been producing large numbers of deaths in detention.

The international community should also prepare a plan for addressing the severe economic needs of the people of North Korea. Under the most optimistic scenario, a package of international economic assistance should be envisioned if new leadership demonstrates a willingness to pursue improvements in North Korea‟s human rights practices. In foreign investment, core labor standards, including the prohibition of forced labor, as established in the ILO Declaration on Fundamental Principles and Rights at Work, must be ensured. At the appropriate time, international aid for „states in transition‟ should be made available to North Korea to help with the establishment of the rule of law, respect for human rights, political parties, an independent media and the other essential features of a democratic society.

Seek a Full Accounting of Foreign Citizens Held in North Korea Against their Will

North Korea‟s admitted government-sponsored abduction of citizens of other nations, and its refusal to allow them to decide their own choice of residence is a clear violation of international law. The Committee for Human Rights has just released an extraordinary report entitled, “TAKEN! North Korea‟s Criminal Abduction of Citizens of Other Countries.” It explains that North Korea‟s policy of abducting foreign citizens dates back to policy decisions made by North Korea‟s founder Kim Il-sung himself, institutionalized in an espionage reorganization by his son Kim Jong-il around 1976.

The abducted came from widely diverse backgrounds, at least twelve nationalities, both genders, and all ages, and were taken from places as far away as London, Copenhagen, Zagreb, Beirut, Hong Kong, and China, in addition to Japan. Initially, over 80,000 skilled professionals were abducted from South Korea during the Korean War. In the 1960s, 93,000 Koreans were lured from Japan and held against their will in North Korea. A decade later, children of North Korean agents were kidnapped apparently to blackmail their parents. Starting in the late 1970s, foreigners who could teach North Korean operatives to infiltrate targeted countries were brought to North Korea and forced to teach spies. Since then, people in China who assist North Korean refugees have been targeted and taken. The staggering sum of foreigners who are held against their will in North Korea is at least 180,308.

In addition, many South Korean families have been separated since the Korean War, and more recently famine, extreme poverty, and political persecution in the North have led to the flight of North Koreans who are then separated from their families. Although North Korea has allowed brief visits under closely-supervised family reunions, only 1,600 of the 125,000 South Korean applicants have been able to participate. Some ten million await information about missing family members. The ICRC should be brought in to use its expert tracing facilities to learn the whereabouts of the missing.

Broaden United States Policy on North Korea to Include Bilateral and Multilateral Approaches to Human Rights Issues

I would like to congratulate Amb. Robert King for his recent visit to North Korea. He is doing what a special envoy for North Korean human rights issues should do—representing the President in obtaining the release of a detained citizen of the United States, and speaking openly about human rights issues directly with officials in Pyongyang. All too often in dealing with North Korea, concerns about peace and nuclear disarmament have taken a priority over the defense of human rights. However, precedents exist for integrating human rights concerns into policies toward countries where nuclear weapons occupy a central point of discussion. Both Democratic and Republican administrations have found effective bilateral and multilateral means of promoting human rights goals with the Soviet Union even though they were negotiating nuclear weapons agreements with its leaders at the same time. Broader discussions about political, economic, energy, human rights and humanitarian concerns have the potential to create a more solid foundation for talks about nuclear issues.

The United States should raise human rights concerns and seek North Korean agreement on specific steps forward, such as: 1) International monitoring of food distribution to ensure it reaches the intended recipients; 2) Accelerated and expanded family reunifications; 3) Decriminalization of movement within North Korea and across the border, and an end to the persecution of those who return voluntarily or are forced back into North Korea; 4) The release of innocent children and family members of those convicted of political crimes; 5) Access to prisoners by the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), the World Food Program (WFP) and other international agencies; 6) Reviews of the cases of prisoners of conscience with the ICRC or Amnesty International with a view to their release; and 7) Identification and provision of a full accounting of prisoners of war from the Korean War and abductees missing from South Korea, Japan, and other nations. While these steps do not address the full range of 8 human rights abuses committed by the North Korean regime, we believe they represent human rights issues that can be raised in negotiations with the regime.

U. S. multilateral initiatives and discussions should also give prominence to North Korean human rights issues. North Korea has ratified five international human rights treaties, has recently placed the term “human rights” in its Constitution, and has participated to a very limited degree in UN reviews of its human rights record. The U. S. should recognize and build on the obligations that the North Korean government has undertaken in international agreements. It should express strong support for the recommendations on North Korean human rights contained in Secretary-General Ban Ki Moon‟s and reports of the Special Rapporteur and press a broad range of other governments to do likewise.

The misery suffered by the people of North Korea is often dismissed as being too difficult to deal with. With good reason, many people conclude that the regime in North Koreais impervious to external pressure. Yet there are initiatives that can be taken to signal that the regime‟s abuse of its own people is a matter of global concern and must be stopped. As I have discussed above, there are also near-term measures that can be taken to alleviate the plight of those who have fled North Korea.

Madame Chairman, your Committee‟s concern for the rights of the people of North Korea has been an inspiration for many years. It has led to the enactment of the NKHRA in 2004, its extension in 2008, and its strong enforcement today. It has been my honor to testify before you. I can only hope that in the very near future the people of North Korea will have the freedom to read what you have done on their behalf and express their views freely in hearings like this themselves.

In this submission, HRNK focuses its attention on the following issues in the DPRK: The status of the system of detention facilities, where a multitude of human rights violations are ongoing. The post-COVID human security and human rights status of North Korean women, with particular attention to sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV). The issue of Japanese abductees and South Korean prisoners of war (POWs), abductees, and unjust detainees.

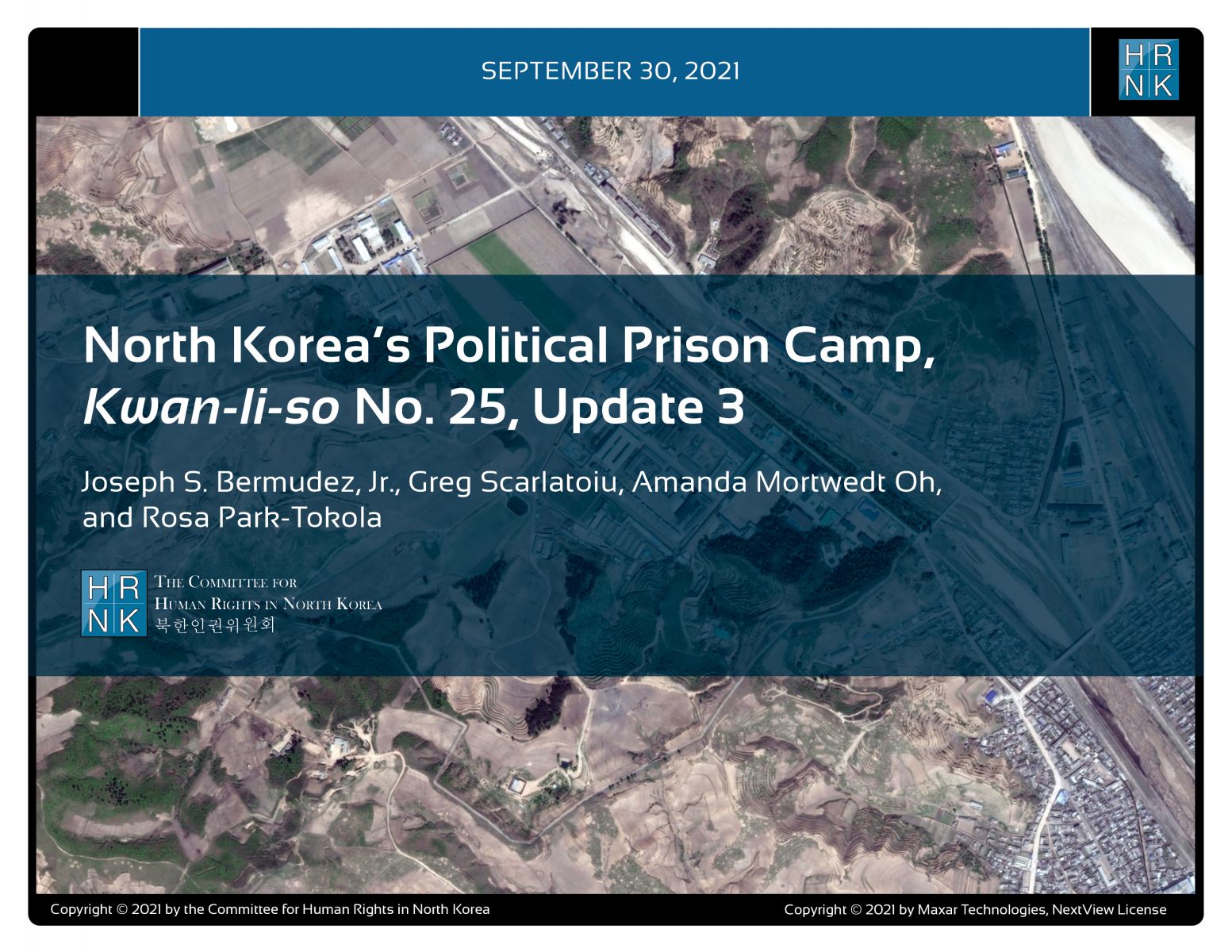

This report provides an abbreviated update to our previous reports on a long-term political prison commonly identified by former prisoners and researchers as Kwan-li-so No. 25 by providing details of activity observed during 2021–2023. This report was originally published on Tearline at https://www.tearline.mil/public_page/prison-camp-25.

This report explains how the Kim regime organizes and implements its policy of human rights denial using the Propaganda and Agitation Department (PAD) to preserve and strengthen its monolithic system of control. The report also provides detailed background on the history of the PAD, as well as a human terrain map that details present and past PAD leadership.

HRNK's latest satellite imagery report analyzes a 5.2 km-long switchback road, visible in commercial satellite imagery, that runs from Testing Tunnel No. 1 at North Korea's Punggye-ri nuclear test facility to the perimeter of Kwan-li-so (political prison camp) no. 16.

This report proposes a long-term, multilateral legal strategy, using existing United Nations resolutions and conventions, and U.S. statutes that are either codified or proposed in appended model legislation, to find, freeze, forfeit, and deposit the proceeds of the North Korean government's kleptocracy into international escrow. These funds would be available for limited, case-by-case disbursements to provide food and medical care for poor North Koreans, and--contingent upon Pyongyang's progress

For thirty years, U.S. North Korea policy have sacrificed human rights for the sake of addressing nuclear weapons. Both the North Korean nuclear and missile programs have thrived. Sidelining human rights to appease the North Korean regime is not the answer, but a fundamental flaw in U.S. policy. (Published by the National Institute for Public Policy)

North Korea’s forced labor enterprise and its state sponsorship of human trafficking certainly continued until the onset of the COVID pandemic. HRNK has endeavored to determine if North Korean entities responsible for exporting workers to China and Russia continued their activities under COVID as well.

George Hutchinson's The Suryong, the Soldier, and Information in the KPA is the second of three building blocks of a multi-year HRNK project to examine North Korea's information environment. Hutchinson's thoroughly researched and sourced report addresses the circulation of information within the Korean People's Army (KPA). Understanding how KPA soldiers receive their information is needed to prepare information campaigns while taking into account all possible contingenc

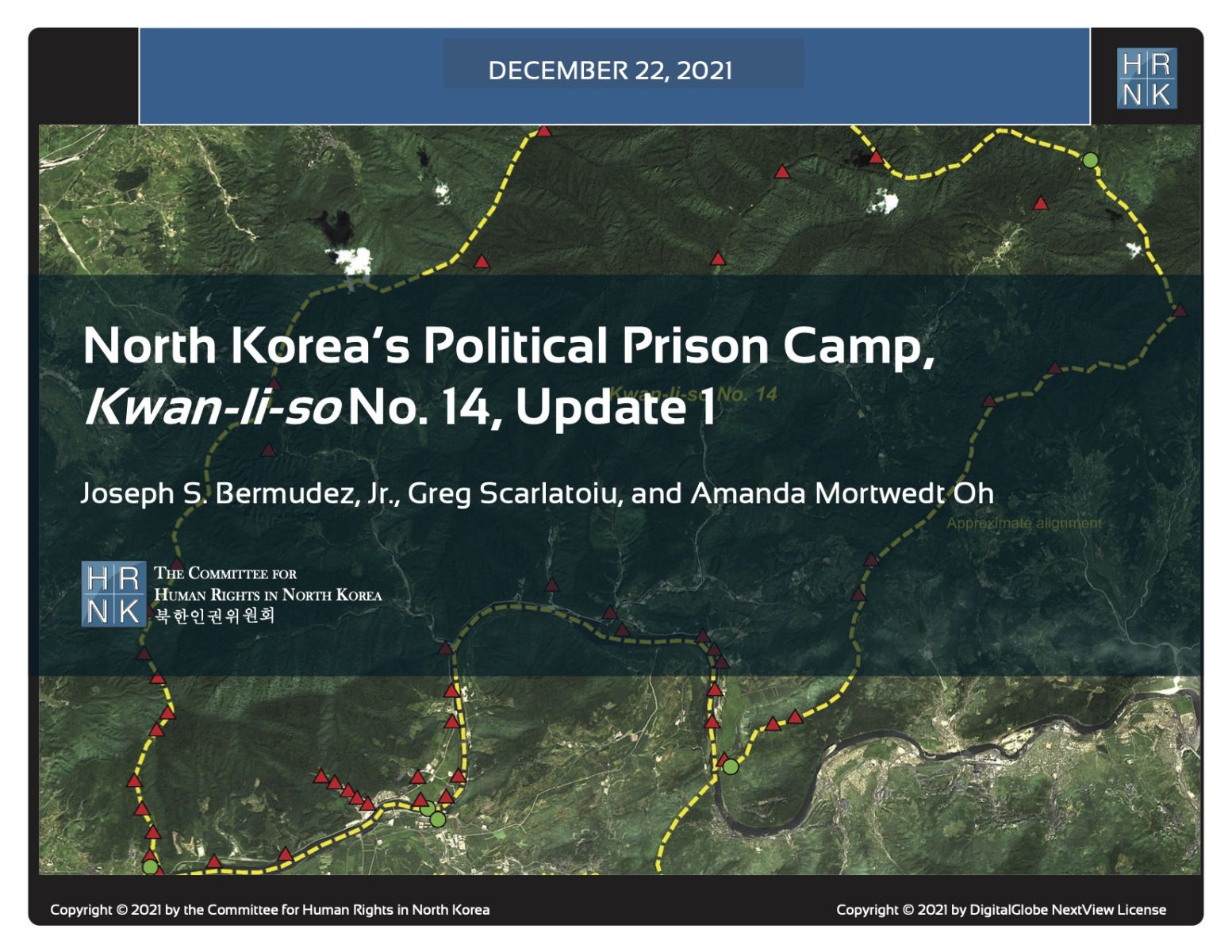

This report is part of a comprehensive long-term project undertaken by HRNK to use satellite imagery and former prisoner interviews to shed light on human suffering in North Korea by monitoring activity at political prison facilities throughout the nation. This is the second HRNK satellite imagery report detailing activity observed during 2015 to 2021 at a prison facility commonly identified by former prisoners and researchers as “Kwan-li-so No. 14 Kaech’ŏn” (39.646810, 126.117058) and

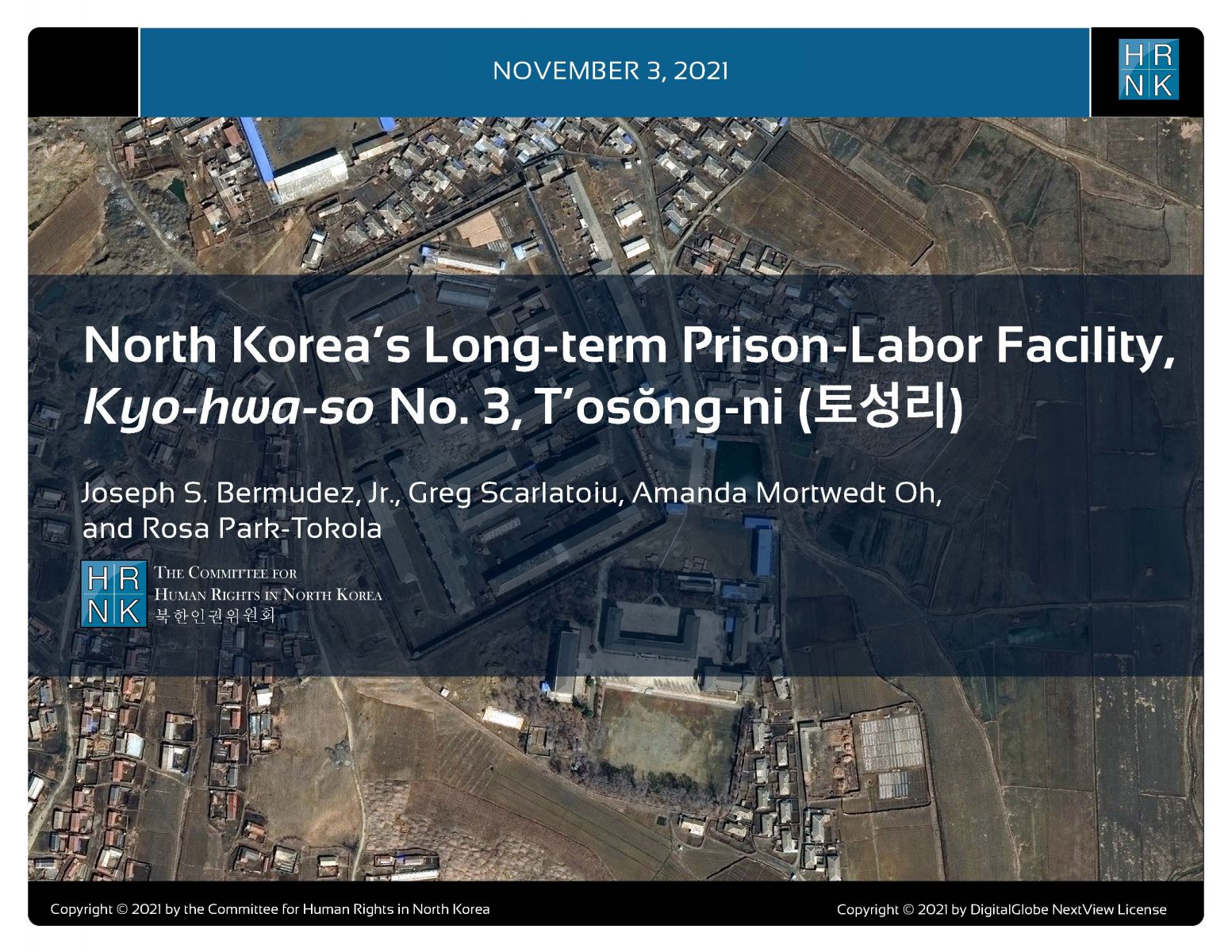

This report is part of a comprehensive long-term project undertaken by HRNK to use satellite imagery and former prisoner interviews to shed light on human suffering in North Korea by monitoring activity at civil and political prison facilities throughout the nation. This study details activity observed during 1968–1977 and 2002–2021 at a prison facility commonly identified by former prisoners and researchers as "Kyo-hwa-so No. 3, T'osŏng-ni" and endeavors to e

This report is part of a comprehensive long-term project undertaken by HRNK to use satellite imagery and former detainee interviews to shed light on human suffering in the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK, more commonly known as North Korea) by monitoring activity at political prison facilities throughout the nation. This report provides an abbreviated update to our previous reports on a long-term political prison commonly identified by former prisoners and researchers as Kwan-li-so

Through satellite imagery analysis and witness testimony, HRNK has identified a previously unknown potential kyo-hwa-so long-term prison-labor facility at Sŏnhwa-dong (선화동) P’ihyŏn-gun, P’yŏngan-bukto, North Korea. While this facility appears to be operational and well maintained, further imagery analysis and witness testimony collection will be necessary in order to irrefutably confirm that Sŏnhwa-dong is a kyo-hwa-so.

"North Korea’s Long-term Prison-Labor Facility Kyo-hwa-so No. 8, Sŭngho-ri (승호리) - Update" is the latest report under a long-term project employing satellite imagery analysis and former political prisoner testimony to shed light on human suffering in North Korea's prison camps.

Human Rights in the Democratic Republic of Korea: The Role of the United Nations" is HRNK's 50th report in our 20-year history. This is even more meaningful as David Hawk's "Hidden Gulag" (2003) was the first report published by HRNK. In his latest report, Hawk details efforts by many UN member states and by the UN’s committees, projects and procedures to promote and protect human rights in the DPRK. The report highlights North Korea’s shifts in its approach

South Africa’s Apartheid and North Korea’s Songbun: Parallels in Crimes against Humanity by Robert Collins underlines similarities between two systematically, deliberately, and thoroughly discriminatory repressive systems. This project began with expert testimony Collins submitted as part of a joint investigation and documentation project scrutinizing human rights violations committed at North Korea’s short-term detention facilities, conducted by the Committee for Human Rights